Two who stood up

The temper of the times

On several occasions President Roosevelt volunteered an opinion of Joseph Stalin.

In 1943, when former ambassador to the Soviet Union, William C. Bullitt, warned Roosevelt about the ambitions of that nation and the man who headed it, Roosevelt responded: “I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of man. Harry [Hopkins] says he’s not and that he doesn’t want anything except security for his own country, and I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won’t try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace.”

In a Fireside Chat delivered to the nation on July 28, 1943: “The world has never seen greater devotion, determination, and self-sacrifice than have been displayed by the Russian people and their armies, under the leadership of Marshal Joseph Stalin. With a Nation which in saving itself is thereby helping to save all the world from the Nazi menace, this country of ours should always be glad to be a good neighbor and a sincere friend in the world of the future.“

In a letter to Churchill: “I think there is nothing more important than that Stalin feel that we mean to support him without qualification and at great sacrifice.”

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, as quoted by British Field Marshal Alan Brooke: “of one thing I am certain; Stalin is not an imperialist.”

At a meeting with his cabinet after returning from Yalta Roosevelt noted that since Stalin had studied for the priesthood, “something entered into his nature of the way in which a Christian gentleman should behave.”

When the Roosevelt administration established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union for the first time in1933, William C. Bullitt was appointed ambassador. Initially a Soviet enthusiast, he soured on the regime as he came to know it. In 1936 Roosevelt replaced Bullitt with Joseph Davies, whose positive view of Stalin remained unshaken by what he witnessed in Moscow. After attending one of the show trials in 1938 Davies commented, “the Kremlin’s fears [regarding treason in the Party and the Army] were well justified“. In a memo he wrote: “Communism holds no serious threat to the United States. Friendly relations in the future may be of great general value.” Elsewhere he described Communism as “protecting the Christian world of free men“, and urged all Christians “by the faith you have found at your mother’s knee, in the name of the faith you have found in temples of worship” to embrace the Soviet Union. When his ambassadorship was over he wrote a book called Mission to Moscow, in which he had nothing but praise for Stalin and the nation he headed. “He gives the impression of a strong mind which is composed and wise. A child would like to sit on his lap and a dog would sidle up to him.” The book was turned into a movie in 1943 to create sympathy for the the United States’ ally of the moment.

Harry Hopkins was probably the closest of Roosevelt’s advisers to the extent that he actually took up residence in the White House in May of 1940. He was also known for his Soviet sympathies. At a rally in June 1942 he promised: “We are determined that nothing shall stop us from sharing with you [the Soviet Union] all that we have.” At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, an event remembered in retrospect for the extent to which the severely ill Roosevelt was buffaloed by the robust Stalin, Hopkins advised: “Mr. President, the Russians have given in so much at this conference I don’t think we should let them down. Let the British disagree if they want – and continue their disagreement at Moscow.”

On the other hand …

There were those who knew better. Some of them because they’d been part of the Soviet effort to infiltrate federal agencies in order to get inside information about the United States government and to influence its policies.

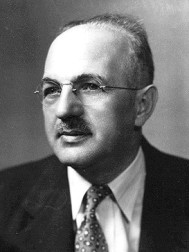

Whittaker Chambers was born in 1901 in Philadelphia to a family of modest circumstances. He joined the Communist Party at the age of 24 while he was a student at Columbia University. Looking back on that time, he offered some thoughts on why he’d done what he’d done, and they reveal a bit about the intellectual cast of his mind:

Whittaker Chambers was born in 1901 in Philadelphia to a family of modest circumstances. He joined the Communist Party at the age of 24 while he was a student at Columbia University. Looking back on that time, he offered some thoughts on why he’d done what he’d done, and they reveal a bit about the intellectual cast of his mind:

.

.

.

.

.

“In the West, all intellectuals become Communists because they are seeking the answer to one of two problems: the problem of war or the problem of economic crises. …

“In the days when I joined the Communist Party [1925], it could offer those who joined it only the certainty of being poor and pariahs. During the 1930’s and 1940’s, when Communism became intellectually fashionable, there was a time when Communist Party patronage could dispose of jobs or careers in a number of fields. … Almost without exception such men and women [who got jobs as a result of their Communist connections] could have made their careers much more profitably and comfortably outside the Communist Party. …

“Few Communists have ever been made simply by reading the works of Marx and Lenin. The crisis of history makes Communists; Marx and Lenin merely offer them an explanation of the crisis and what to do about. …

“It is in the name of that will to survive the crisis…that the Communist first justifies the use of terror and tyranny…

“Terror is an instrument of socialist policy if the crisis was to be overcome…

“Only in Communism had I found any practical answer at all to the crisis, and the will to make that answer work.”

For six years Chambers worked openly in the Communist Party. He took a job with the Party’s newspaper, The Daily Worker, starting out by collecting payments, graduating from that humble task to become a writer and editor until he chose to resign over a disagreement about party politics. He then submitted some stories to the Communist magazine, The New Masses,which were such a hit with the Party’s higher-ups that he was invited to become its editor. The following year a representative of Soviet military intelligence suggested he leave the open party and accept a position in the underground. Chambers said no, only to discover that the “suggestion” had really been more of an order. After thinking it over, he decided to yield to party discipline. For the next seven years he worked as a spy, initially doing routine tasks in transmitting documents from local espionage agents to the Soviet Union. Having demonstrated his loyalty and competence, in 1934 he was given duties of much greater importance – liaison between an array of covert Communists in federal agencies and their foreign controllers. The people with whom Chambers became involved had been organized by a man named Harold Ware. “Once the New Deal was in full swing,” Chambers later wrote, “Hal Ware was like a man who has bought a farm sight unseen only to discover that the crops are all in ready to harvest. All that he had to do was to hustle them into the barn. The barn in this case was the Communist Party. In the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, Hal found a bumper crop of incipient or registered Communists…. The immediate plan called for moving the ‘career Communists’ out of the New Deal agencies, which the party could penetrate almost at will, and their gradual infiltration of the old-line departments, with the State Department as the first objective.” One early member of the Ware group was a lawyer named Alger Hiss with whom Chambers would become close friends and who did manage to move to a position in the State Department. The degree of penetration the Soviets achieved at that time was such that the head of the underground in the United States confided to Chambers, “Even in Germany under the Weimar Republic, the party did not have what we have here.”

Chambers, however, wasn’t the ideological robot Hiss would prove to be. In 1936 his curiosity was aroused by a minor news item about a general in the Red Army who’d been shot for treason. This led him to inquire about the purges then underway in Moscow and to his being told by his Soviet controller that asking such questions could put a person in line to be shot. It took a major effort for him to overcome his years of ideological conditioning, but Chambers was driven by that response to get a copy of I Speak for the Silent and read it through. The more he learned about what the Communists had been doing since the revolution, the greater his disillusionment became until he reached the point that he knew had to get out. In April of 1938 he abandoned his post in the underground and his connection with the Party. Aware of others who’d been assassinated for such things, he deserted the house he’d been living in and went on the run with his wife and child. The need to earn a living forced him back into public life though, just in time to accept a position a friend had found for him with Time Magazine.

He started the job in April of 1939. In August the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Germany, making likely a war in Europe in which the United States might become involved. Presuming the Soviets would share the results of their espionage efforts with their German allies, Chambers decided he had to let the President know what had been going on. He got a journalist friend named Isaac Don Levine to arrange a meeting, not with Roosevelt, as it turned out, but with Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle. At the meeting Chambers gave Berle the names of twenty or so espionage agents and clandestine Soviet sympathizers in positions of sufficient importance to be dangerous to the nation’s safety. Alger Hiss was one of them. Berle scribbled notes on everything Chambers said and appeared to take the warning seriously. Months passed though and nothing happened, so Chambers checked back with Levine. “Adolf Berle, said Levine, had taken my information to the President at once. The President had laughed. When Berle was insistent, he had been told in words which it is necessary to paraphrase, to ‘go jump in the lake.‘”

Two years later, FBI agents visited Chambers at Time. Although they’d come to see him about another matter entirely, Chambers assumed they were there as a result of the meeting he’d had with Berle in 1939 and told them of the notes the latter had taken at that time. That got Chambers the attention not only of the FBI but of the Civil Service Commission and Office of Naval Intelligence, whose agents stopped by to question him on various subsequent occasions. From 1946 through 1948 Chambers was contacted with increasing frequency by the FBI about people he’d named in his meeting with Berle. As it turned out, the G-men were confirming testimony they’d received from a more recent defector – a woman whose career in the underground had overlapped with his but that he’d never heard of.

Elizabeth Bentley was born to a prosperous family in Connecticut in 1908. She graduated from Vassar, spent a year in Italy and returned to the United States, jobless in the Depression year of 1934. Among the friends she made while looking for work was an enthusiastic Communist who urged her to join the Party. Bentley took the step in 1935 and was surprised to discover how many of the people she knew were already secret Communists, as she herself became when she adopted the alias, Elizabeth Sherman.

Elizabeth Bentley was born to a prosperous family in Connecticut in 1908. She graduated from Vassar, spent a year in Italy and returned to the United States, jobless in the Depression year of 1934. Among the friends she made while looking for work was an enthusiastic Communist who urged her to join the Party. Bentley took the step in 1935 and was surprised to discover how many of the people she knew were already secret Communists, as she herself became when she adopted the alias, Elizabeth Sherman.

.

.

.

.

Her reasons for joining constitute an interesting contrast with the more intellectual ones that Chambers wrote of. Bentley was driven by emotions that had been aroused in her through the good-heartedness and righteous rhetoric of the Party members she’d come to know personally. “They [Communists] seemed to be continually engaged, at the sacrifice of a considerable amount of time and energy, in humanitarian projects, such as better housing for the poor, more relief for the underprivileged, and higher wages for the workers. It is they, I thought, who are the modern Good Samaritans. It is they who are putting into practice the old Christian ideals that I was brought up on.” She also wanted to fight Fascism, a party she’d come to know and oppose during her stay in Italy. The reasons for that opposition aren’t clear though, given the fact that the sponsorship of public works, the resulting creation of jobs and state control of economic matters generally were features Fascism shared with Communism, along with the government’s ability to make sure its policies were followed through a reliance on dictatorial powers. But then Bentley was able to draw on an experience she’d actually had under Fascism, but not under Communism.

In 1936 the purge of early Bolsheviks and the show trials that accompanied them were under way in Moscow – the event that led Chambers to re-evaluate his commitment to Communism. Bentley was still firmly in the Party’s intellectual grasp, however. “As far as I remember,” she recalls, “none of us Communists ever questioned the charge that these men were traitors and criminals.”

Four years after joining the Party, Bentley was introduced to a man named Jacob Golos, a member of the secret police, she would later discover, with an impressive history of achieving Communist goals by whatever means it took and prone to justify in retrospect any endeavors done in the interests of the Soviet Union. When Golos told Bentley to cut her connections with the open Party so she could work for him in the underground, she did as he ordered; and it didn’t take long for the two of them, working as closely as they did, to fall in love. Golos had a wife and son in the Soviet Union, but marriage was a worn-out remnant of bourgeois morality, after all, so it presented no barrier to their taking up life together. Bentley’s responsibilites included helping Golos manage a couple of shipping businesses in New York to provide money for the Party and serve as a cover for espionage. Curiously, it wasn’t until May of 1941, more than two years after she’d started her collaboration with Golos, that it dawned on Bentley she was no longer working for Communists in the United States but for the Soviet Union. When Germany invaded that country a month later, Golos was ordered to, “get as many trusted comrades as possible into strategic positions in United States government agencies in Washington, where they will have access to secret and confidential information that can be relayed to the Soviet Union.” “Knowing all the risks involved,” he asked her, “are you still willing to go on with me?” Whether it was the United States she was serving or the Soviets was no longer of concern. She’d come to accept whatever Golos told her. “I had made my choice and I would stick to it. ‘Of course,’ I answered quietly.“

Four years after joining the Party, Bentley was introduced to a man named Jacob Golos, a member of the secret police, she would later discover, with an impressive history of achieving Communist goals by whatever means it took and prone to justify in retrospect any endeavors done in the interests of the Soviet Union. When Golos told Bentley to cut her connections with the open Party so she could work for him in the underground, she did as he ordered; and it didn’t take long for the two of them, working as closely as they did, to fall in love. Golos had a wife and son in the Soviet Union, but marriage was a worn-out remnant of bourgeois morality, after all, so it presented no barrier to their taking up life together. Bentley’s responsibilites included helping Golos manage a couple of shipping businesses in New York to provide money for the Party and serve as a cover for espionage. Curiously, it wasn’t until May of 1941, more than two years after she’d started her collaboration with Golos, that it dawned on Bentley she was no longer working for Communists in the United States but for the Soviet Union. When Germany invaded that country a month later, Golos was ordered to, “get as many trusted comrades as possible into strategic positions in United States government agencies in Washington, where they will have access to secret and confidential information that can be relayed to the Soviet Union.” “Knowing all the risks involved,” he asked her, “are you still willing to go on with me?” Whether it was the United States she was serving or the Soviets was no longer of concern. She’d come to accept whatever Golos told her. “I had made my choice and I would stick to it. ‘Of course,’ I answered quietly.“

Bentley now became engaged in the kind of liaison work that Chambers had graduated to before his defection. She and Golos operated under the overall control of the NKVD, however, while Chambers had been part of a parallel but separate espionage effort run by military intelligence. Once immersed in her new duties, Bentley told Golos how impressed she was at the number of people he’d been able to enlist as quickly as he had. “Very simple,” the man told her, “this organization has been built up solidly over a period of years and is always ready in case of emergency.” Looking back on her activities of the time, Bentley confirmed the strategy Chambers had enunciated. “Many of the contacts we took on as agents were already in government service. If they were in positions that we considered productive, we left them where they were, otherwise we encouraged them to pull strings and move into more sensitive agencies.“

Most of Bentley’s undercover contacts were dues paying members of the Party, although some chose to remain outside as sympathetic hangers-on. The most important of the groups she dealt with was centered in the Treasury Department, having been organized by an Agriculture employee named Greg Silvermaster. Bentley also came to know and know of an extensive array of other agents, many of whom had been in Chambers’ circle or on its periphery. These shared contacts later allowed the recollections of Chambers and Bentley to be compared and confirmed. Among the more prominent officials who had connections with both Bentley and Chambers were Harry Dexter White, an Under Secretary of theTreasury; Lauchlin Currie, an adviser to President Roosevelt on economics and China; and Alger Hiss, a State Department employee whom Bentley knew of but only second hand.

By 1943 Bentley’s feelings for Golos had come to transcend her attachments to the Party and the Soviet Union. It was his continuing dedication to Communism that drove her to work as hard as she did. But something happened that put Golos at odds with his supervisors. It might have stemmed from his failing health, but he attributed the problem to a drastic falling off in the quality of NKVD personnel. Whatever the reason, he was ordered to turn over to new Soviet agents his American contacts – people as crucial to his work as Silvermaster, for example, with whom he’d created a bonds of trust and friendship by long and careful cultivation. He was even asked to consider separating his work from Bentley’s. Neither he nor she was willing to contemplate demands of that sort, so by Thanksgiving of 1943 Golos found himself faced with handing over his contacts in three days or being branded a traitor. That night he died of a heart attack in Bentley’s presence.

She was devastated. The person who’d been the primary motivation for her work was dead – killed, as she saw it, by pressures put on him by fools in the NKVD. She’d been in the movement long enough to continue her duties robotically, but now she was confronted with having to do what Golos had been ordered to. She sought help from Earl Browder, a friend who’d headed the Communist Party of the United States. When Browder deferred to the Soviets, Bentley was left without an ally of sufficient influence to give her any hope of defying her adversaries. This led her to ask herself if she wanted to continue her work in the underground and her association with the Party. She’d known agents who’d gone bad and been killed for it, so she had no illusions about the possible consequences. On the other hand she was angry enough to seriously consider the opportunity the FBI gave her to get back at the people who’d betrayed her and the man she’d loved. In August of 1945 Elizabeth Bentley paid a secret visit to the FBI office in New Haven, Connecticut.

She was devastated. The person who’d been the primary motivation for her work was dead – killed, as she saw it, by pressures put on him by fools in the NKVD. She’d been in the movement long enough to continue her duties robotically, but now she was confronted with having to do what Golos had been ordered to. She sought help from Earl Browder, a friend who’d headed the Communist Party of the United States. When Browder deferred to the Soviets, Bentley was left without an ally of sufficient influence to give her any hope of defying her adversaries. This led her to ask herself if she wanted to continue her work in the underground and her association with the Party. She’d known agents who’d gone bad and been killed for it, so she had no illusions about the possible consequences. On the other hand she was angry enough to seriously consider the opportunity the FBI gave her to get back at the people who’d betrayed her and the man she’d loved. In August of 1945 Elizabeth Bentley paid a secret visit to the FBI office in New Haven, Connecticut.

.

The reasons for Bentley’s defection constitute an even greater contrast with those of Chambers than had her reasons for joining. They certainly weren’t based on an acknowledgment that she and Golos had been laboring for the forces of evil. In fact the people against whom she sought revenge were the ones who’d tried to interfere with that work. “We thought we were fighting to build a better world,” she wrote later, “and instead we are just pawns in another game of power politics, run by men who are playing for keeps and don’t care how they get where they’re going. It was for this shabby thing that Yasha [Jacob Golos] fought and gave his life – now I knew the answer to the awful struggle he had gone through the last days of his life. He had discovered what was really going on, but he was too broken then to want to live any longer. They had killed him, these people, killed one of the most decent people that had ever lived!“

Once she’d decided to change sides, she did allow herself to delve into the darker aspects of Communism’s past. She became more critical of the Soviet Union and less so of the United States. But her primary motivation remained personal and emotional. It was because of what they’d done to her and her man, that she wanted to bring down around the ears of the people who ran it, the extraordinarily successful espionage apparatus that had been established years earlier. Remarkably enough, in that effort this lone enraged individual largely succeeded.

Starting in November of 1945, while continuing to work in the Soviet underground, Bentley met periodically with FBI agents, who took the information she gave them and combined it with their own research to create an enormous file on clandestine Soviet intelligence activities, including data on the approximately 150 people whose names she’d supplied. The extent of Bentley’s revelations led to her being called to testify before a grand jury in New York in July of 1947. By then almost two years had passed since her defection, and the Soviet espionage operation had come to a standstill as a result of their undercover agents being told to lie low. Bentley continued her work with the Grand Jury for the better part of a year, after which she was invited to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (usually abbreviated HUAC). It was then – July of 1948 – that the newspapers picked up her story and overnight Elizabeth Bentley became “the Red Spy Queen”.

Party politics

In order to understand what happened next, it’s useful to have some feel for the political forces in play at the time. When Bentley went to the FBI late in 1945, Harry Truman had been president for less than six months, but Democrats had occupied the White House for more than twelve years. The war was over. Germany and Japan were no longer enemies of the United States, and it was becoming clearer every day that the country’s erstwhile ally, the Soviet Union, was not the agent of progress and democracy Roosevelt and his advisers had led the nation to believe. To the extent it could be shown to exist, Communist infiltration of government agencies would no longer be dismissed as an irrelevant fancy, and blame for it would be laid at the feet of the people who’d let it happen. Truman viewed international Communism as more of a threat than Roosevelt had, but if the man from Missouri was anything, it was a partisan politician. His Justice Department was not about to acknowledge the state of affairs that Elizabeth Bentley’s testimony indicated had come into being during the last decade.

In order to understand what happened next, it’s useful to have some feel for the political forces in play at the time. When Bentley went to the FBI late in 1945, Harry Truman had been president for less than six months, but Democrats had occupied the White House for more than twelve years. The war was over. Germany and Japan were no longer enemies of the United States, and it was becoming clearer every day that the country’s erstwhile ally, the Soviet Union, was not the agent of progress and democracy Roosevelt and his advisers had led the nation to believe. To the extent it could be shown to exist, Communist infiltration of government agencies would no longer be dismissed as an irrelevant fancy, and blame for it would be laid at the feet of the people who’d let it happen. Truman viewed international Communism as more of a threat than Roosevelt had, but if the man from Missouri was anything, it was a partisan politician. His Justice Department was not about to acknowledge the state of affairs that Elizabeth Bentley’s testimony indicated had come into being during the last decade.

.

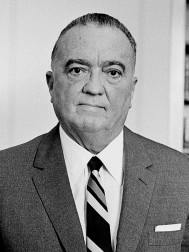

What complicated things for Truman was the fact that the FBI and its director, J. Edgar Hoover, didn’t share his desire to hush things up. Roosevelt had been faced with the same problem, but the mood of a nation at war and his own popularity made it easier for the Commander in Chief to act imperiously. Even before Bentley came forward, the FBI had accumulated an enormous amount of information about Communist penetration of federal agencies. Bentley’s revelations made action on them just that much more urgent. On the other hand, Truman held the aces and he knew it. The FBI was part of the Justice Department. Hoover took his orders from the Attorney General and the Attorney General from the President. What may have caused the president a bit of concern was his uncertainty about Hoover’s willingness to stick with the chain of command. But Truman needn’t have worried. Rather than going public with what he knew, Hoover kept shoving information at Truman and the people around him in the form of new and more elaborate reports, realizing all the while that they could choose to do what they did and push the information aside.

What complicated things for Truman was the fact that the FBI and its director, J. Edgar Hoover, didn’t share his desire to hush things up. Roosevelt had been faced with the same problem, but the mood of a nation at war and his own popularity made it easier for the Commander in Chief to act imperiously. Even before Bentley came forward, the FBI had accumulated an enormous amount of information about Communist penetration of federal agencies. Bentley’s revelations made action on them just that much more urgent. On the other hand, Truman held the aces and he knew it. The FBI was part of the Justice Department. Hoover took his orders from the Attorney General and the Attorney General from the President. What may have caused the president a bit of concern was his uncertainty about Hoover’s willingness to stick with the chain of command. But Truman needn’t have worried. Rather than going public with what he knew, Hoover kept shoving information at Truman and the people around him in the form of new and more elaborate reports, realizing all the while that they could choose to do what they did and push the information aside.

The Justice Department ran the Grand Jury investigation to which Bentley’d given evidence. The outcome they aimed for was that her information would appear to have been thoroughly explored but contain nothing worthy of criminal charges. Interestingly enough that’s exactly what happened. A year of Bentley’s testifying led to exactly zero (0!) indictments. In a court of law it would only be her word against that of the accused, the prosecting attorney could point out to anybody who chose to ask about the vacuous result. And that would have seemed plausible in light of the testimony actually taken. But the prosecutors were as aware as the FBI of the availability of Chambers to back Bentley up, and of Louis Budenz as well – another turned-around Communist who’d known many of Bentley’s people. The prosecuting attorney consciously chose not to call either of those men or indeed anybody else capable of supporting Bentley’s charges.

What the Grand Jury did next was launch an investigation of the leaders of the open and legal Communist Party. In that effort they succeeded in getting eleven (11!) indictments under the Smith Act – a law enacted in June 1940 when war with Germany, the Soviet Union or both seemed imminent, providing the impetus to include as one of the act’s provisions that it was a crime to advocate violent overthrow of the government. The only purpose in trying Communist Party officials for that offense would be to show the newspaper-reading public that Truman’s Justice Department was plenty tough on Communism, so tough that in going after those particular rascals they were willing to brush aside the Constitutional guarantees everybody else was entitled to in being able to put their beliefs, however obnoxious, into speech and print.

Republican Congressmen, meanwhile, were at least as concerned as Hoover about the real threat to the government through Soviet infiltration. And not only were those Congressmen not subject to the control of the Attorney General, they’d be only too happy to bring to light any scandalous conditions that could plausibly be traced to the Democrats.

Chambers and Hiss

During July of 1948 Bentley was quizzed by HUAC, which then included first term Republican Representative Richard Nixon. In August the Committee called Chambers to confirm and expand on what Bentley’d told them. Chambers started his testimony August 3. During the course of the day’s questioning he mentioned Alger Hiss as one of the undercover Communists he’d dealt with. To give Hiss a chance to respond, the Committee asked him to appear on August 5. Hiss, who now held the position of President of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, stated categorically that he’d never been a Communist, never known Whittaker Chambers and didn’t recognize a photo of the man. In fact Hiss conducted himself with such self-assurance that most of the Committee’s members thought they’d been had by Chambers, ought to dump him as a witness and go on to somebody else. It was Nixon who talked them out of it. One of the two witnesses had to be lying and it was up to the Committee to figure out which it was, since it was as clear as day that nobody else ever would. So three weeks of questioning went by with directly contradictory statements from the two men and a personal confrontation staged between them. Hiss wound up doing a lot of backpedalling and tap-dancing and finally did claim to have known Chambers but under the name of “Crosley”; but nothing more damaging came of it than that. Chambers remained unequivocal about Hiss’s membership in the Party but steered clear of mentioning espionage. On August 25 HUAC concluded its questioning of the two with no recommedation for action against either one – for espionage, perjury or anything else. Hiss had plenty of friends in high places who continued to praise his character and insist he’d been maligned, but for those who took a look at the information the Committee had elicited and the means they’d had to use to get it, Chambers had the clear edge in believability.

Testimony to Congressional committees is protected against being treated as libelous. Hiss challenged Chambers to repeat what he’d told HUAC in a setting where he could be sued for what he said. This Chambers did on the television show, Meet the Press, on August 27. After considering his options for a month, Hiss followed up on his threat and sued Chambers on September 27. The Chambers-Hiss confrontation had already become a major news event. The lawsuit made it moreso. A Grand Jury charged with investigating Communist activities could no longer choose to ignore Chambers. As soon as he’d been served with a summons for the libel suit, he received another from the Grand Jury. What wasn’t clear, was whether the Justice Department hoped to draw on his knowledge of the Soviet underground to go after Hiss and people like him, or if it was Chambers they wanted to indict, to put an end to all the charges he’d been making that were now garnering a lot of unwelcome attention.

On November 4 there was a pre-trial hearing for the libel suit that was to have enormous consequences. As a routine measure in making evidence known to both sides, Chambers was instructed by Hiss’s lawyers to turn over to them any letters or other communications he had from Alger Hiss. Although the requesting attorneys had no notion of what they’d invited, Chambers had in fact squirreled away 65 pages of State Department documents illegally synopsized and copied by Hiss. He retrieved these papers, along with some rolls of microfilm whose contents he couldn’t remember, from the home of a relative where he’d left them ten years earlier. At the next pre-trial hearing on November 17 he turned the papers but not the film over to Hiss’s lawyers. The documents made clear what Chambers had refrained from saying: the two had clearly been involved in espionage. At the instigation of Hiss’s lawyers, copies of the papers were given to the Justice Department, an agency that had been reliably protective of Hiss’s interests.

Keep in mind that Chambers was now caught up in three different government procedures, each with its own purpose, each with a cast of characters that would defend its interests against those of the other two. He was a witness for the House of Representatives’ Committee on Un-American Activities, a witness for the Justice Department’s Grand Jury, and the defendant in the civil suit initiated by Alger Hiss.

A couple of weeks passed. On December 1 an item appeared in the Washington Post that Chambers had come up with evidence of major importance in the libel suit. HUAC’s Chief Investigator, Robert Stripling showed up at Chambers’ farm the same day to ask what was up. Chambers said he couldn’t reveal anything about a case in progress, but Stripling had Chambers come by his office the next day where the latter was presented with a subpoena requiring him to “turn over to the House Committee on Un-American Activities any evidence whatever that I might possess which related in any way to the Hiss Case.” Viewing the Committee as an ally against the Justice Department, Chambers readily complied by retrieving the rolls of microfilm from a hollowed out pumpkin on his property where he’d hidden them overnight. Enlargements of the film resulted in a stack of evidence four feet high. The promptness with which Stripling had acted was clearly inspired by his determination to keep any other evidence Chambers might have from falling into the hands of the Justice Department.

Justice struck back by having the FBI spirit Chambers away to a private office to be grilled at length about the microfilm he’d given to HUAC as well as some other matters the Justice Department was interested in. Chambers was also handed a subpoena requiring him to appear before the Grand Jury immediately, forestalling any attempt by HUAC to lay prior claim to his testimony. But Nixon and the Committe weren’t about to back off. The tension between the two factions came to a head at New York’s Pennsylvania Station when members of HUAC and the Justice Department got into a shouting match that led to an agreement under which Justice got photostats of some of the microfilm and HUAC was allowed to interview Chambers in private before his next Grand Jury appearance.

Justice struck back by having the FBI spirit Chambers away to a private office to be grilled at length about the microfilm he’d given to HUAC as well as some other matters the Justice Department was interested in. Chambers was also handed a subpoena requiring him to appear before the Grand Jury immediately, forestalling any attempt by HUAC to lay prior claim to his testimony. But Nixon and the Committe weren’t about to back off. The tension between the two factions came to a head at New York’s Pennsylvania Station when members of HUAC and the Justice Department got into a shouting match that led to an agreement under which Justice got photostats of some of the microfilm and HUAC was allowed to interview Chambers in private before his next Grand Jury appearance.

.

.

What the people in the Attorney General’s office had set out to do was evident in the memos they sent to the FBI at this time, requesting an investigation to determine if Chambers had committed perjury but no parallel effort concerning Hiss. Nevertheless, it was the FBI that did the Justice Department’s investigating, and the men in that bureau had no compunctions about following lines of evidence that would put Alger Hiss in a bad light. Nixon and Stripling meanwhile made it clear they wouldn’t hesitate to resort to the Committee’s headline-grabbing ability if Hiss were handed a free pass. Chambers and Hiss both testified. The evidence against Hiss was persuasive, but the crucial last link was to show that Hiss had had access to the typewriter on which the damning documents had been typed, and that device had not been located. On December 7, with a week to go in its term, the Grand Jury didn’t find the evidence conclusive enough to indict. Over the weekend of the 11th and 12th the FBI came up with other papers known to have been typed in Hiss’s household. When the typefaces were compared, the typewriters were shown to be the same. This seems to have been the crucial link in the Justice Department’s decision about which man to go after, and it certainly inspired the prosecution’s next step. If certain facts can be shown to be true, then asking questions about those facts can sometimes be used to induce perjury. The federal prosecutor asked Hiss specific questions about the typed documents and the period of time during which Hiss had been in contact with Chambers, to which Hiss had to lie to be consistent with his earlier testimony. On December 15, the last day of its term, the Grand Jury indicted Hiss on two counts of perjury.

Chambers wasn’t off the hook, but the prosecution had effectively been confronted with a choice of which man to indict. They had started out wanting to it to be Chambers in spite of the fact that it was he who had renounced the errors of his past and voluntarily placed himself in danger of going to jail in order to make amends for what he’d formerly been involved in. But the evidence showed what it showed, and the surrounding political situation wasn’t as controllable as the President might have liked. The case against Hiss was clear. Indicting Chambers as well would undermine the credibility of the chief witness in that case. Chambers held his breath, but he wasn’t indicted. So ended 1948.

During the course of the next year Hiss was tried twice. Under Judge Kaufman, Prosecutor Murphy and Defense Attorney Stryker, the jury hung on a vote of 8 to 4 for conviction. Retried under Judge Goddard, Prosecutor Murphy and Defense Attorney Cross, Hiss was convicted unanimously of two counts of perjury on January 21, 1950. He went to jail in March 1951. His libel suit against Chambers was dismissed the following month.

Aftermath

By the time of Bentley’s defection in 1945, the opportunity to prevent the most dramatic consequences of Soviet penetration had gone by the boards. If Roosevelt had taken to heart the situation that Chambers’ conversation with Berle had disclosed in 1939, the aftermath of World War II might have been different. To suggest a few possibilities, Alger Hiss wouldn’t have been at Yalta in February 1945 to hold the hand of two-months-in-office Secretary of State Edward Stettinius; Harry Dexter White wouldn’t have had the ear of Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau in plotting Germany’s postwar fate, Lauchlin Currie wouldn’t have helped decide which of the contending factions in China would be rewarded and which stiffed; and the Soviet Union wouldn’t have exploded an atomic bomb as early as August 1949.

As Chambers was to write a few years after the excitement of his encounter with Hiss has subsided, “Most of the Communists in the Hiss Case, like most of those in the Bentley case, are going about their affairs much as always. It is not the Communists, but the ex-Communists who have cooperated with the Government who have chiefly suffered. All of the ex-Communists who co-operated with the Government had broken with the party entirely as a result of their own conscience years before the Hiss Case began.” A handful of individuals were actually tried and convicted of Communist related activities: Alger Hiss and William Remington for perjury, Carl Marzani for lying on his government application, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for passing atom bomb secrets to the Soviet Union, for which the latter two were executed. Bentley’s revelations did have the effect of shutting down the espionage operation that the Soviets had been conducting so successfully until then. What was not as dramatically affected was the influence admirers of Communism continued exert from inside. In spite of a Loyalty Program put into effect by an executive order of President Truman, the manner in which individuals with documented Communist ties disappeared from government rolls remained much as it had been until 1948: they were pressured to resign but allowed to leave without penalty. If there’s something anti-Communist agitators can take consolation from, it’s the fact that many did move on. On the other hand, the extreme discreetness of their departures obscured from the newspaper-reading public the degree to which allegations of infiltration had had substance; and, since nothing went into the folder of a resigning employee to indicate that he’d been asked to resign or why, he was free to seek a different job in the government or with an agency that had strong ties to the government.

As Chambers was to write a few years after the excitement of his encounter with Hiss has subsided, “Most of the Communists in the Hiss Case, like most of those in the Bentley case, are going about their affairs much as always. It is not the Communists, but the ex-Communists who have cooperated with the Government who have chiefly suffered. All of the ex-Communists who co-operated with the Government had broken with the party entirely as a result of their own conscience years before the Hiss Case began.” A handful of individuals were actually tried and convicted of Communist related activities: Alger Hiss and William Remington for perjury, Carl Marzani for lying on his government application, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for passing atom bomb secrets to the Soviet Union, for which the latter two were executed. Bentley’s revelations did have the effect of shutting down the espionage operation that the Soviets had been conducting so successfully until then. What was not as dramatically affected was the influence admirers of Communism continued exert from inside. In spite of a Loyalty Program put into effect by an executive order of President Truman, the manner in which individuals with documented Communist ties disappeared from government rolls remained much as it had been until 1948: they were pressured to resign but allowed to leave without penalty. If there’s something anti-Communist agitators can take consolation from, it’s the fact that many did move on. On the other hand, the extreme discreetness of their departures obscured from the newspaper-reading public the degree to which allegations of infiltration had had substance; and, since nothing went into the folder of a resigning employee to indicate that he’d been asked to resign or why, he was free to seek a different job in the government or with an agency that had strong ties to the government.

It was in fact the half-heartedness of this approach to security that led to the subsequent involvement of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Being a senator rather than a representative, McCarthy had no direct connection with HUAC. The post from which he would go on to conduct his inquiries was as chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate’s Government Operations Committee. As a Republican, however, he had the same political motivations as the Republicans in HUAC in exposing Democratic malfeasance. Starting from a list of 108 potential security risks in the State Department that had been compiled by the House Appropriations Committee two years earlier, he and his staff added some names of their own and set about checking the current status of the people enumerated. Many were found to be still working for or in collaboraton with the government, leading Senator McCarthy to declare in a speech he delivered in Wheeling, West Virginia on February 9, 1950 that “I have in my hand 57 cases of individuals who would appear to be either card carrying Communists or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still helping to shape our foreign policy.” There was then and remains to this day controversy about the words McCarthy actually spoke from the podium in Wheeling, but not concerning what he’d intended to say, since he clarified the matter when questioned about it later. It took a few days for the reaction to build, but from February 20, 1950 until McCarthy was censured by the Senate in December of 1954 on two abstruse charges, he would be continually engaged in investigations of two sorts: those he conducted to expose what he believed to be government security risks, and those (5 of them) conducted by his Senate colleagues to expose what they believed to be the impropriety of his methods.

It was in fact the half-heartedness of this approach to security that led to the subsequent involvement of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Being a senator rather than a representative, McCarthy had no direct connection with HUAC. The post from which he would go on to conduct his inquiries was as chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate’s Government Operations Committee. As a Republican, however, he had the same political motivations as the Republicans in HUAC in exposing Democratic malfeasance. Starting from a list of 108 potential security risks in the State Department that had been compiled by the House Appropriations Committee two years earlier, he and his staff added some names of their own and set about checking the current status of the people enumerated. Many were found to be still working for or in collaboraton with the government, leading Senator McCarthy to declare in a speech he delivered in Wheeling, West Virginia on February 9, 1950 that “I have in my hand 57 cases of individuals who would appear to be either card carrying Communists or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still helping to shape our foreign policy.” There was then and remains to this day controversy about the words McCarthy actually spoke from the podium in Wheeling, but not concerning what he’d intended to say, since he clarified the matter when questioned about it later. It took a few days for the reaction to build, but from February 20, 1950 until McCarthy was censured by the Senate in December of 1954 on two abstruse charges, he would be continually engaged in investigations of two sorts: those he conducted to expose what he believed to be government security risks, and those (5 of them) conducted by his Senate colleagues to expose what they believed to be the impropriety of his methods.

(M. Stanton Evans, Blacklisted by History)

The cost of standing up

As people who’d been in the Party long enough to have seen what had happened to other apostates, Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers may not have been surprised at the degree of vilification to which they were subjected by Communists and their intellectual allies. The nature of the allegations followed the prescribed pattern so predictably as to be comical if they hadn’t also been so vicious: sexual proclivities too shameful to be spoken of out loud, drunkenness, insanity, and, politically, crytpo-fascism.

Elizabeth Bentley died in of cancer in 1963 at the age of 55. She had documented her experience in joining and working for the Soviet underground and her decision to leave it in an intriguing 1951 memoir called Out of Bondage. What sets her book apart from other accounts of lapsed Communists is the degree of personal – as opposed to political – motivation it reveals: her feelings for Jacob Golos in particular, but the other friendships and enmities she developed within the party, and the apparent ease with which she managed to switch political allegiance when she felt betrayed by the people for whom she’d labored long and hard.

Elizabeth Bentley died in of cancer in 1963 at the age of 55. She had documented her experience in joining and working for the Soviet underground and her decision to leave it in an intriguing 1951 memoir called Out of Bondage. What sets her book apart from other accounts of lapsed Communists is the degree of personal – as opposed to political – motivation it reveals: her feelings for Jacob Golos in particular, but the other friendships and enmities she developed within the party, and the apparent ease with which she managed to switch political allegiance when she felt betrayed by the people for whom she’d labored long and hard.

.

.

.

Whittaker Chambers died of a heart attack in 1961 at the age of 60. In 1952 he’d published his autobiography, Witness, in which he describes how he’d been drawn into the Communist world, his work in the open and underground Party, his disillusionment and subsequent determination to take a stand against what he’d come to regard as philosophical blight of the age, realizing, as he put it, that he was leaving the winning side for the losing one. As a professional writer he was well equipped for the task, but what he achieved in the book transcended what might have been expected. In detailing his sojourn through the political enthusiasms of his era, he allows us to discover as he did the nature of the spiritual collapse that had led to the emergence of Communism in the 19th century and the consequences that had in his century, the 20th, in helping to make it the most governmentally murderous of all time.

Whittaker Chambers died of a heart attack in 1961 at the age of 60. In 1952 he’d published his autobiography, Witness, in which he describes how he’d been drawn into the Communist world, his work in the open and underground Party, his disillusionment and subsequent determination to take a stand against what he’d come to regard as philosophical blight of the age, realizing, as he put it, that he was leaving the winning side for the losing one. As a professional writer he was well equipped for the task, but what he achieved in the book transcended what might have been expected. In detailing his sojourn through the political enthusiasms of his era, he allows us to discover as he did the nature of the spiritual collapse that had led to the emergence of Communism in the 19th century and the consequences that had in his century, the 20th, in helping to make it the most governmentally murderous of all time.

.

.

National heroes

From the United States of the 1930’s and 40’s various individuals linger in public memory. In the cultural realm such people as playwright Lillian Hellman, author Ernest Hemingway, and folksinger Woody Guthrie are still honored; in science J. Robert Oppenheimer for the work he did in helping to create the atomic bomb; while in the politics, Franklin Roosevelt remains dominant.

From the United States of the 1930’s and 40’s various individuals linger in public memory. In the cultural realm such people as playwright Lillian Hellman, author Ernest Hemingway, and folksinger Woody Guthrie are still honored; in science J. Robert Oppenheimer for the work he did in helping to create the atomic bomb; while in the politics, Franklin Roosevelt remains dominant.

.

.

.

.

.

Neither Whittaker Chambers nor Elizabeth Bentley is much remembered though. Mention their names to a hundred people and most will never have heard of either one, although Chambers retains some lingering fame from the notoriety of his confrontation with Hiss. Of those who do remember Chambers or Bentley, the most likely comment will be, “Oh, yeah. Didn’t he have something to do with the start of McCarthyism?”

One way of judging a nation is by the people it comes to regard as heroes. Once an idol becomes established in the public mind, there’s a good chance he’ll wind up being depicted in a government memorial, often in Washington D.C. There his bronze or marble image will invite the admiration of passers-by …

One way of judging a nation is by the people it comes to regard as heroes. Once an idol becomes established in the public mind, there’s a good chance he’ll wind up being depicted in a government memorial, often in Washington D.C. There his bronze or marble image will invite the admiration of passers-by …

.

.

.

.

.

.

safely insulated from time’s caprices and those pesky reminders of what the person it represents actually did.

.

.

The worst government ever

.

.