Flimflam 1: the Depression

click on a picture to enlarge it and see its title

Flimflam 1: the Depression

The United States had gone through a lot of economic downturns since its founding, those of 1819, 1837, 1873, 1893, and 1907 being among the ones identified as “panics” in the language of the day – with that of 1920 having been the most recent of significance prior to 1929. The question is: why did it take till the end of the third decade of the 20th century for the most devastating economic collapse of all to occur and what made it as bad as it was?

Given what we know of human psychology with its ambitions and enthusiasms on the one hand, its regrets and recriminations on the other, most of us aren’t surprised that economic conditions produced by the combined actions of millions of people show the same kinds of ups and downs as the fortunes of individuals. In fact economic matters are probably more subject to erraticism than personal ones, given the degree to which they depend on borrowed money and the difficulties people have in foreseeing their ability repay, the capricious ways value is attached to such things as precious metals, jewels and works of art, and even more so to the foundations of investment like stocks and real estate. To say nothing of the intrusions of government and the impacts of events unforeseen.

Okay, you say, but the uncertainties inherent in lending money, evaluating investments and encountering life’s surprises have been around since the founding of the Republic and well before. People had learned to live with bumps in the economic road as much as in all the other byways of life. They’d come to realize that downturns induced by failures of confidence and unanticipated events often got extended by the kind of mob psychology people are prone to; but having been through events of that sort a few times, they also realized that financial collapses contain the seeds of their own reversal. When apparent wealth evaporates in, say, a stock market crash, some of what happens turns out to be useful. You have less money to the pay for things you’d planned on, to hire people and pay their salaries, and, maybe most regretfully, to meet your debts; so you wind up buying fewer things, firing unneeded workers, offering lower wages to those who stay on, and defaulting on your obligations or threatening to. All of which send prices and wages lower and unemployment higher. But it’s those naturally occurring adjustments that make goods more affordable, workers more hirable, partial payments more likely to be accepted on old debts and interest rates lower on new ones. As the feeling of panic subsides, people find prices have declined enough to allow them to buy more of what they need. Sales pick up, then so do jobs and wages. If this sounds like Pollyanna playing the glad game, keep in mind it’s the results that have been witnessed over time and the reasons for them figured out by reasoning backward. Prior to 1929, recessions occurred with moderate frequency, but the bottoms were usually brief, 12 to 18 months maybe, and things got back to pre-crisis levels in a couple of years, five at most.

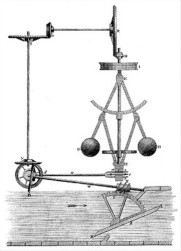

Nobody liked the ups and downs, but they viewed them as much a part of life as catching cold or getting stuck in a rain shower or a traffic jam. Experience demonstrated that when individuals were allowed to act separately and freely in the ways they viewed as in their best interests, downturns brought on by occasional over-enthusiasms resulted in feedback of the sort that a thermostat relies on to bring a household back to its proper temperature or an engine’s governor to its proper speed.

Nobody liked the ups and downs, but they viewed them as much a part of life as catching cold or getting stuck in a rain shower or a traffic jam. Experience demonstrated that when individuals were allowed to act separately and freely in the ways they viewed as in their best interests, downturns brought on by occasional over-enthusiasms resulted in feedback of the sort that a thermostat relies on to bring a household back to its proper temperature or an engine’s governor to its proper speed.

.

.

.

.

A little history

To see why 1929 turned out to be different we need to take a look at how the concept of government that prevailed in the United States had changed since the nation’s founding. The American Revolution was unique in seeking to give people as much freedom as was consistent with the orderly resolution of disputes and protection from aggression. At least that was the premise on which the Constitution was based even when it wasn’t scrupulously adhered to. That spirit was reflected in the sparseness of the economic duties assigned to Congress in Article I, Section 8: “To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures“. With the tenth amendment’s guarantee that, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people,” those few tasks were all that the federal government was allowed to do.

To see why 1929 turned out to be different we need to take a look at how the concept of government that prevailed in the United States had changed since the nation’s founding. The American Revolution was unique in seeking to give people as much freedom as was consistent with the orderly resolution of disputes and protection from aggression. At least that was the premise on which the Constitution was based even when it wasn’t scrupulously adhered to. That spirit was reflected in the sparseness of the economic duties assigned to Congress in Article I, Section 8: “To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures“. With the tenth amendment’s guarantee that, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people,” those few tasks were all that the federal government was allowed to do.

Four months after George Washington became the first president of the United States, rioters in Paris invaded the Bastille, signaling the start of a series of revolutions that took a completely different approach to government, one aimed at providing benefits to social and economic classes that had been short-changed under Europe’s monarchies. Government was assigned the task of identifying the problems of its constituents and coming up with ways to solve them by whatever means that might entail. Predictably this led to increased control over people’s lives, and, since poverty and the distribution of wealth were prominent among the issues considered, manufacturing, farming, employment, ownership and economic matters in general, were given special attention, all of which led to the emergence of varying degrees and flavors of socialism.

Four months after George Washington became the first president of the United States, rioters in Paris invaded the Bastille, signaling the start of a series of revolutions that took a completely different approach to government, one aimed at providing benefits to social and economic classes that had been short-changed under Europe’s monarchies. Government was assigned the task of identifying the problems of its constituents and coming up with ways to solve them by whatever means that might entail. Predictably this led to increased control over people’s lives, and, since poverty and the distribution of wealth were prominent among the issues considered, manufacturing, farming, employment, ownership and economic matters in general, were given special attention, all of which led to the emergence of varying degrees and flavors of socialism.

.

By 1924 the legacy of the French Revolution was reflected in the accession of the first nominally socialist government in England, while more extreme examples had already been installed by Communists in Russia and Fascists in Italy.

.

Having started from a different political heritage and being separated from Europe by the width of an ocean, the United States was slow to accept the notion of government as definer and corrector of society’s ills. By 1907, however, the idea had caught on to the extent that a sharp but brief financial downturn and associated bank failures led Congress to seek a remedy in legislation. Despite the fact that the Constitution made no provision for such a thing, more than a century of teasing unintended powers out of bland phrases allowed Congress to bring the Federal Reserve System (FRS) into being. The newly created agency consisted of a dozen banks in cities across the country under the overall direction of a Board of Governors in Washington. Its purpose was to oversee the nation’s monetary and banking systems.

.

A little economics

One of its expected benefits was the elimination of business cycles and the bank failures they often entailed. To achieve this the FRS was given the ability to make loans to commercial banks at rates set by its Board. More significantly it could also increase the supply of money in the same way that a counterfeiter does, by printing new bills. In practice the FRS more often emulated the check writing techniques of a forger – paying for bonds it bought with credits it created out of thin air and deposited into the seller’s account. These invented dollars not only added their value to that of the money in existence, they could also be used to back up loans. Banks earn their keep by charging interest on what they lend to customers; and it was the FRS that specified what percentage of a loan had to be kept on hand to accommodate withdrawals by the bank’s depositors. If the FRS chose to cut the reserve requirement in half, say from 20 percent to 10, a bank could double the amount it lent out with the same amount of backing, putting twice as much money into the hands of its borrowers.

When the amount of money increases relative to the value of goods and services it represents in financial transactions, the effect is called “inflation”, even though it’s customarily measured indirectly by adding up the cost of a particular collection of products rather than the ratio of all-the-dollars to what-those-dollars-stand-for. When the FRS adds to the money supply, it takes a while for the new funds to work their way into the system from the accounts into which they’ve been deposited, but once that happens consumers find it takes more dollars than it used to to buy the same items: each one is worth less. By reversing the transactions used to increase the amount of money, the FRS can just as easily decrease it. The result is deflation. Fewer dollars will then be necessary to make the same purchases: each one is worth more.

Governments get involved in two kinds of economic activity: monetary and fiscal. The former is concerned with the forms of money, its quantity and the way it’s backed. In the United States these functions are under the control of the FRS. Attitudes prevalent in Europe led to the notion that a government can also serve useful purposes by fiscal measures – how it puts money to use – for example by sponsoring public works to create jobs. In the United States the executive and legislative branches both engage in fiscal matters when they specify who gets taxed and how much, which public programs get funded and which don’t, and what rewards are granted and penalties imposed on individuals and businesses to influence their economic behavior.

The FRS started operation in November of 1914, three months after the outbreak of World War I. The conditions that prevailed in Europe by the end of that war and the emergence of the United States as a major economic power gave the agency more importance than it had at its inception. The first important test of its influence on business cycles came with a drop in prices and wages that took place in the middle of 1920, accompanied by an upsurge in unemployment and a decrease in the money supply. The FRS responded in predictable fashion by creating money to compensate for what had been lost in the contraction. The economic downturn proved to be brief. It was over in one year with employment back to normal in another. It was in the middle of that slump that Warren Harding became president. He named Andrew Mellon his Secretary of the Treasury and Herbert Hoover his Secretary of Commerce. Of the three it was Hoover who’d become enamored of using fiscal measures for political ends, but the quickness of the recovery made the plans he’d devised unnecessary. There were lessons to be learned from the incident, however. The existence of the FRS hadn’t kept the recession from happening, but the agency did seem to serve a useful purpose in making money available when it fell into short supply. Fiscal measures hadn’t proved necessary, so their value remained debatable.

A decade of solid prosperity elapsed before a series of dramatic stock market declines at the end of October 1929 let the public know that a new recession was underway – one of particular severity. By this time Herbert Hoover had become president. Now he’d have a chance to test his theories. As things turned out, the combined responses of the Federal Reserve and two presidential administrations produced some of the most boneheaded policies ever inflicted on an unsuspecting populace by people who passed themselves off as experts. Looking back from 90 years, we can laugh at their pretensions. For the people who had to live through it, the laughs came hard.

Big D

The FRS responded to the crisis as expected by creating money and easing credit. For reasons hard to fathom, the Board then reversed its policy and let the money supply decline during 1930 and even more dramatically in the two years that followed, so that by the beginning of 1933 a third of the money in circulation in 1929 had ceased to exist. Deflation is good for lenders, lousy for debtors since the latter have to pay off their loans with dollars worth more than the ones they’d borrowed. In tough times, of course, any amount of money is hard to come by, and when a borrower defaults it hurts both him and the lender. But the FRS failed in ways other than letting the money supply go down. When the economy takes a turn for the worse, the depositors of a bank, especially a small one, start to wonder about its financial stability. They can cause a “run” if all of them try to withdraw their money at the same time, and that can sink the bank since most of its deposits are out on loan. Before 1914, big banks helped little ones in situations like that by extending them credit. Some banks stayed afloat by simply refusing withdrawals until they’d had time to replenish their reserves – awarding themselves a “holiday” – even though they may have been in violation the law when they did it. The strategy didn’t always work, but it did save a lot of banks before the FRS was established. When a lifeguard comes on duty, swimmers head for deeper water since they don’t have to rely on their friends to pull them out if conditions get rough. By 1929 the big banks were letting the little ones look after themselves since the FRS had gone on duty as a lender of last resort. A spate of bank failures started around the end of 1930 though, and it continued on and off through the next couple of years. What was the FRS doing all this time? Good question. Credit was predictably hard to come by during the Depression, but at the end of 1931 the FRS made things even tougher for the banks it was supposed to be helping by raising interest rates more than it ever had on the loans it offered them. Banks continued to fail, with a particularly severe period in the interval between Roosevelt’s election in November of 1932 and his taking office four months later. It wasn’t until 1934 that confidence was restored and runs became rare when the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created. A government agency could provide safety of a sort commercial banks couldn’t. The FDIC was able to draw on funds collected by coercion. Taxpayers who’d chosen not to trust banks with their savings wound up buying insurance for those who had. It wasn’t fair but it solved a problem. Nobody bothered to complain.

Hoover 1929-1933

The older I get the more I’m convinced that the judgments of history are never right. My mother told me never to say never though, and maybe she had a point: given the law of averages, once in a while the historians have got to at least come close. “Once in a while“, I said – not this time. Hoover stood by while the Depression did its worst, they tell us, then Roosevelt got elected and put an end to it with a slew of imaginative programs. That’s how they put it in the book I was taught out of – honest.

Whatever Hoover’s shortcomings may have been, they didn’t include not trying to overcome the Depression. What he wound up doing made things worse though, so he can be criticized for trying too hard.

Whatever Hoover’s shortcomings may have been, they didn’t include not trying to overcome the Depression. What he wound up doing made things worse though, so he can be criticized for trying too hard.

Within a couple of weeks of the crash Hoover called a series of meetings with businessmen and coaxed them into keeping wages at pre-Depression levels. This was supposed to help not only people they employed but the economy as a whole by allowing demand to stay high. People with protected wages made out like bandits. It was the rest of the population that had to pick up the tab for their good fortune. High wages mean high prices. With national income down, consumers couldn’t afford to buy as much as they used to. Demand declined and so did the number of employees needed to meet it. Protected wages for some meant being out-of-work for others. After all though, what would you expect when you purposely cut the link between wages and prices?

.

.

.

.

Relying on the logic that led to propping up wages, Hoover decided to prop up prices as well. This time it was farmers he was out to save. The Federal Farm Board (FFB) bought up products they viewed as “surplus” in the sense that the quantity available resulted in lower prices per unit. The artificial demand induced by FFB purchases did keep prices higher than they would have been, not only for the people who were trying to sell the crops they’d raised, of course, but also for the ones who were trying to buy them to feed their families. It also led farmers to grow even more of what the FFB had set out to cut back on. The government’s response to too much cotton, was to tell cotton farmers to grow less. When, predictably, that didn’t work, officials had them plow a third of what they’d planted back into the dirt. While most of the nation was scrambling to afford the basics of life, cotton farmers were out in the fields, destroying what they’d grown. And why not? That’s what the experts paid them to do, after all; and who in his right mind would want lower prices?

What else did voters need protection from? How about foreign competition? Hoover got Congress to jack up tariffs in 1930 with a bill named for its sponsors, Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley. The U.S.’s trading partners naturally struck back with higher tariffs of their own. Just when consumers were trying to get the lowest prices they could, bargains on imports disappeared along with overseas markets for U.S. products. You couldn’t exactly call the new tariffs unfair because everybody was made to suffer. And Hoover came up with one more way to get in good with the locals: he had immigration cut.

Tax receipts went down when productivity and income did, but Hoover wasn’t about to give up on spending money to keep the economy in motion. He upped the budget each year from 1929 to 1932, a combined 40% over the interval, creating a deficit in every year but the first. By 1932 he figured he had to do something about the growing debt though, so he got Congress to pass one of the biggest peacetime tax increases ever. All sorts of taxes went up – excise, corporate, inheritance and you-name-it – together with across the board increases on income. For the lowest brackets – yearly incomes under $8000 – marginal rates more than doubled, while the maximum went from 25% to 63%.

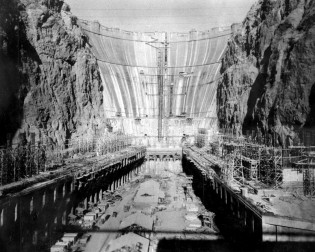

When times are hard people need every dollar they can put their hands on just to afford the basics. And they have to be allowed to spend their money as they choose. Dollars are votes. How people put their hard-earned income to use conveys better than any theory or speculation what it is they actually need and want. It tells farmers and manufacturers what to produce, employers who to hire, and the unemployed what skills to acquire. Taxes do just the opposite. They take money out of the hands of people who’ve earned it and let an office-bound official decide what to spend it on and what jobs to create in the process. During Hoover’s tenure tax revenues were channeled into a bunch of expensive long-term projects like the San Francisco Bay Bridge, the Los Angeles Aqueduct and Boulder (later Hoover) Dam, all of whose benefits lay years in the future, while the labor those dollars were being converted into did nothing to address the current needs of the Depression’s sufferers.

When times are hard people need every dollar they can put their hands on just to afford the basics. And they have to be allowed to spend their money as they choose. Dollars are votes. How people put their hard-earned income to use conveys better than any theory or speculation what it is they actually need and want. It tells farmers and manufacturers what to produce, employers who to hire, and the unemployed what skills to acquire. Taxes do just the opposite. They take money out of the hands of people who’ve earned it and let an office-bound official decide what to spend it on and what jobs to create in the process. During Hoover’s tenure tax revenues were channeled into a bunch of expensive long-term projects like the San Francisco Bay Bridge, the Los Angeles Aqueduct and Boulder (later Hoover) Dam, all of whose benefits lay years in the future, while the labor those dollars were being converted into did nothing to address the current needs of the Depression’s sufferers.

You say I’m being too hard on Hoover. Okay, use whatever words you want to to describe the results of his fiscal interventions. You can’t hide the fact that they produced the worst economic record in the nation’s history.

Roosevelt 1933-1945

Roosevelt took office at what proved to be the low point of the Depression. Unemployment was around 25% and the banking system was in shambles. The new president launched a dizzying array of programs aimed at improving things, and he certainly got the public’s attention with his damn-the-torpedoes way of going about them.

Roosevelt took office at what proved to be the low point of the Depression. Unemployment was around 25% and the banking system was in shambles. The new president launched a dizzying array of programs aimed at improving things, and he certainly got the public’s attention with his damn-the-torpedoes way of going about them.

Just two days after being sworn in, for example, he declared a week long “bank holiday”. All the banks in the country had to shut down and re-open only as regulators allowed. The idea was to forestall failures by forcing banks to catch their breaths in the same way that those in trouble had chosen to do individually during earlier panics. A lot of states had already tried the idea, but Hoover had resisted it at a national level because of the disruptions it caused: not just a few banks unavailable for a day or two but all of them for an extended period, and not just the depositors’ ability to withdraw funds but the whole range of banking services. Beyond that, it established a new precedent for federal control. It wouldn’t be up to individual bankers to decide when to re-open. Government officials would tell them if and when they could.

.

.

.

Was the holiday a success? Since 1929 the number of banks had shrunk from 25,000 to 18,000. Fewer than 12,000 were able to re-open within ten days of the start and only 3,000 more did so later, leaving a net loss of 3,000 banks during the holiday. Granted some were absorbed in mergers and others eventually paid back most of their customers’ deposits, the moratorium didn’t put an end to failures, but it did seem to boost public confidence in the banks that survived. The real solution lay a year in the future. States could have chosen to insure bank deposits since doing it at the national level called for a constitutional amendment. But who could be bothered with details like that at a time like this? So they just went ahead and created the FDIC anyway. Constitution be damned; it did solve a problem?

Roosevelt launched a lot of new programs that way, many of them concentrated in the first hundred days of his term: the Emergency Banking Act, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Federal Emergency Relief Act, Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), Tennessee Valley Authority, Federal Securities Act, National Employment System Act, Home Owners Refinancing Act, and the National Industrial Recovery Act which set up the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee all sorts of economic activity. Virtually all of Roosevelt’s initiatives were bigger, more coercive versions of things Hoover had already tried, but they also incorporated the distinctive attitudes of his administration – viewing the federal government as the solver of the nation’s problems, offering employees protection from employers, unions from management, farmers from competition and borrowers from lenders. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” drew on much the same set of sympathies as had motivated Europe’s ventures in socialism.

Despite following in Hoover’s wake, Roosevelt seemed not to have learned much from his predecessor’s mistakes. Like Hoover, he set out to keep wages and prices high, but rather than soliciting the voluntary cooperation of businesses, he had the NRA impose a set of rules euphemistically called a “Code of Fair Competition”.

While many of the projects Hoover funded could be criticized for diverting labor from more urgent needs, Roosevelt’s misdirections outdid those of his predecessor by a country mile.

The Works Project Administration (WPA) invented jobs to fit the interests of the people it brought on board. Out-of-work artists, for example, were paid to paint murals on the walls of post offices, and theater folk to produce dramas they couldn’t have put over commercially but that allowed the participants to express the sympathy many of them felt for the most murderously intolerant and economically inept regime yet to gain control of a nation (the Soviet Union, of course) by sentimentalizing the factions it appealed to and demonizing the ones it treated as enemies.

Sponsoring public art had the advantage that the people who benefited could let their audiences know how much they appreciated a government that paid them to do whatever they wanted to. Some taxpayers did object to the latitude allowed the participants and the flagrance of the propaganda that resulted. The public may have become accustomed to being flimflammed, but it hadn’t yet been lobotomized. Other agencies followed WPA’s lead, dreaming up jobs to suit the people it hired. What more could a teenager ask than to have the CCC send him to a national park to lay out trails for vacationing hikers? Needless to say, the services provided to the public by Roosevelt’s make-work agencies had not been on the shopping lists of the Depression’s victims.

Another area in which Roosevelt easily outstripped the man he’d replaced was in the wholesale destruction of farm products. Following the lead set by the Hoover’s FFB but leaving its predecessor numerically in the dust, the AAA not only paid growers to plow under 10 million acres of cotton and 12,000 of tobacco but to kill 6 million baby pigs at a time when a lot of the population had accustomed itself to going without meat in its diet.

Another area in which Roosevelt easily outstripped the man he’d replaced was in the wholesale destruction of farm products. Following the lead set by the Hoover’s FFB but leaving its predecessor numerically in the dust, the AAA not only paid growers to plow under 10 million acres of cotton and 12,000 of tobacco but to kill 6 million baby pigs at a time when a lot of the population had accustomed itself to going without meat in its diet.

.

.

.

.

Of course not every action of the Roosevelt administration was as inane as the ones I’ve chosen to list here. When the president came up for re-election in 1936, he could cite the fact that virtually all the economic indicators had improved since he took over. Yearly average unemployment had gone from 25% in 1933, to 21.7, then 20.1, winding up at 17% in the election year. Not as rapid as recoveries from earlier panics had been nor as complete, but a lot better than the dreary slide Hoover had had to witness: 3.2% in 1929 followed by 8.9, 15.9, and 23.6, reaching 25% in the year he turned things over to his successor.

So how did Roosevelt manage to do better than Hoover by relying on more grandiose versions of schemes that had already failed? There were some differences of course, a couple of which were significant. The FRS started doing the job it was supposed to by increasing the money supply and making credit easier to get; and the FDIC virtually put an end to bank failures. Hoover had become president with the economy at such an exalted state that, looking back, we’re tempted to think the only way it had to go was down; while Roosevelt had taken charge with things so bad that maybe the reverse was true. And then there were the effects of public relations and public perceptions. Having been in office when the Depression started, Hoover had to take the rap for having caused it. Whether that judgment was fair or not, everything he tried just made things worse. What’s curious is that he wasn’t blamed for the misguidedness of the things he did, but for not doing enough of them. Roosevelt had the advantage of being out of office when the economy went sour. By tying that in with his inherent air of self-assurance, the elaborateness of the program he’d put together, and the sympathy he got from the press, Roosevelt created the impression of a knight coming to the rescue – an image Hoover’s low-key reassurances never remotely approached. If there’s a placebo effect in politics – and the bank holiday was surely an example of one – the medicine Roosevelt dished out benefited from the flair with which he went about it.

A placebo can make people with aches and pains feel better, but it won’t cure them of cancer. Roosevelt came up with enough small victories in his first four years, including a an 8% reduction in unemployment, to beat Alf Landon by the biggest margin of any of his four presidential victories. The timing of that election turned out to have been opportune for the president though. Less than a year later things took a turn for the worse, and by 1938 unemployment was back to 19%. What leads to the conclusion that Roosevelt’s progress had been more cosmetic than substantive is the fact that nine years into the Depression – four under Hoover then five under Roosevelt – the economy wound up in a worse state than it had been in any of its preceding 150 years except for 1932 and 1933. Once unemployment reached 9% in 1931, for the next ten years it stayed above the level it had attained in any previous panic or recession. Judged by economic data, Hoover’s tenure was the worst in history, but Roosevelt’s was a close second.

The greater calamity

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the imposition of military conscription in 1940, and full blown wartime involvement in 1941, the effects of he Depression became lost in the more dire consequences of war. With half a million men in the armed forces in 1940, 2 million in 1941, 4 million in 1942, and 9 million in 1943, unemployment ceased to be a measure of distress. That does invite another question though. How in the devil did the United States manage to get involved in two wars at the same time, both fought thousands of miles from its own borders?

.

.

.

.